Ramsay Historic Features

Below are some of the historical features you'll find in Ramsay. Please click on the links provided below or scroll down to view them all.

- Bolger's Corners

- Indian Hill

- King Edward VII Among the Cedars

- St. George's Cemetery

- The Floating Bridge Mural

- The George Eccles Commemorative Sign

- The Historical Settlement of Bennies Corners

- The Historical Settlement of Leckie's Corners

- The Rosedale Union Hall Cheese Factory Mural

- The Historical Settlement of Union Hall

- The Rosedale Union Hall Cheese Factory

- Union Hall School

- The Union Hall Women's Institute Historical Mural

- The Historical Settlement of Huntersville

Bolger's Corners

Where Clayton Side Road meets Tatlock Rd is often referred to as Bolger’s Corners. On the southeast corner, the farm was owned by the Bolger family of the area, William and Elizabeth Bolger specifically, and hence became known as Bolger’s Corners.

There was a little settlement in that area with the stores of John Bowes and John McWhinnie as well as the Reformed Presbyterian Church that was right at the corner, across the road from the Bolger farm.

The Methodist cemetery and site of the first Methodist Church is often considered to be part of Bolger’s Corner.

In 1841, John Bowes bought 4 acres of NE1/2 Lot 21 Conc 1 which was next to the Methodist cemetery. He also operated the Post Office for a short time. There was a slot in the door as a place to leave letters for mailing. Patrick Murray, a shoemaker, once lived there and shoe laces were found when the house was torn down many years later. In 1850, John Bowes sold his property and moved away.

In 1842, John McWhinnie bought a piece of land, part of Lot 21, Conc2, across the road from John Bowes. He also operated a store amongst his many activities, but in 1846 he declared bankruptcy, selling his place in 1850 and moving away.

The Reformed Presbyterian Church Clayton

From Whispers From The Past – History and Tales of Clayton by Rosemary Sarsfield

The beginning of the Reformed Presbyterian Church in Ramsay was through the efforts of William Moir and James Rae who were known to be preaching in 1823. Soon, Walter Gardner, John McEwen, and James Smith were conducting a “Praying Society”. This Church had its roots in Scotland and was active in America. In 1839, Rev James Mulligan came from Ryegate, Vermont, to preach. He was followed by Robert McKee of New York and John Symmes. Mr. Mulligan organized a congregation of the Reformed Presbyterian Church which continues to this day in the Almonte Reformed Presbyterian Church (Hillside Church). This is the oldest Presbyterian congregation in Ramsay.

Locally, church buildings were built on the eighth line of Ramsay and on the second line of Ramsay. The one on the second line of Ramsay, a log building, was built in 1835. It was located just outside the present Clayton. It was located on land occupied by James Smith in the 1829s (Lot 21, Conc. 2). It was out of use by at least 1847. Concerning its construction, we read:

In those days money was scarce…yet churches were successfully built by division of labour, with very little money. The walls and rafters were put in by combined effort. Certain persons made the shingles, others put them on. One brought the boards, another laid the floor, and still another made the window frames and sash, and this the whole was easily accomplished.

As Rev Robert More, the Reformed Presbyterian minister, did his research in the 1970s on the properties, he took out with him a local older lady, Mrs. Mary Morton, to examine the properties. At the property in Clayton he noted:

Again, Mrs. Morton has seen its ruin as a child. A visit to the spot and a discovering of the old road bed showed that the building sat in the “T” of the road where it turns right to Clayton (from the present Clayton Road onto the Tatlock Road at Bolger’s Corners). The building sat lengthwise in the upper bar and in the left-hand side of the stem. As late as 1880, the old gutted shell was yet observable, but today all trace has disappeared.

The Methodist Church Cemetery in Clayton

Extracts from The Record News – EMC, Friday, October 13, 2000 written by Dianne Pinder.

Officially registered on Saturday, Aug. 27, 1853 “at half past ten of the clock in the forenoon,” the cemetery was also home to the Methodist Church until it burned in 1879 or 1880. The brick house across from St. George’s Church was built as a replacement in 1880 with worship being held there until the 1920s when the Methodists in Canada joined with some of the Presbyterians to form the United Church. Some of the stones from the original foundation of the church remain in the cemetery. The old cemetery fell into neglect and until recently, the Clayton Methodist Cemetery was nothing but brambles, its headstones as forgotten as the memories of those buried there. Thanks to the efforts of two local churches, Guthrie United and St. George’s Anglican – the cemetery has now been restored. The two churches worked together on Saturdays to undo the years of neglect at the tiny cemetery near Bolger’s Corners. It was an intensive undertaking with the dedicated volunteers spending many hours just clearing the massive amounts of brush. “It took us about seven Saturdays to just clear the brush, to cut it,” says Scotty McAskill, who has been one of the “mainstays” of the restoration project. That task was made even more difficult by the fact some of the wire from the old wire fence in front of the cemetery had grown into the trees. The fence was removed with the brush. Once that work was complete, the ground on which the cemetery is situated was leveled off. Charlie Rath, who attends, St. George’s church, donated all the fill for the project. Work was done on cleaning up the headstones and setting the bases back into the ground. Since there is no plot plan for the cemetery, the tombstones were placed “where they are.” Only nine of the original 12 headstones could be located. It is feared a couple may have been stolen. Other stones from the property were added to the stones from the original foundation to “make an imprint” of where the church was. A plaque was also erected at the location. A visit to the cemetery is a trip into history. Among those whose names appear on headstones is Edward Bellamy, the founder of Clayton. The cemetery was also the burial place for a veteran of the War of 1812, James McNiece. Mr. McNiece, who died on Nov. 21, 1850, fought in some of the war’s famous battles – Lundy’s Lane, Sacketts Harbour, Snake Hill and Cook’s Mills. More than 30 years after the war ended, he was credited in 1847 with making a citizen’s arrest of a deserter from the war and taking a reward for turning in the former soldier, Mr. McNiece was given 500 Pound Sterling. “You could write a book on him,” Mr. McAskill says. And on the cemetery as a whole, as the headstones tell much about the hardships of the early settlers who inhabited this area from the three members of the Cunningham family who fell victim to scarlet fever in a one-month period in 1877 to Sophy McClary who was less than a year old when she died in 1864. Her sister Irena, who was born in December, 1865, only lived for three months. The restoration project was undertaken in thanksgiving “for the faith, dedication and perseverance” of the early settlers of Clayton.

Indian Hill

It is believed that there used to be a trading post on the top of the hill where the Indian Hill cemetery is now. When they were digging graves they found the skulls of Indigenous peoples so it came to be called Indian Hill Road. It was the original road from Almonte to Pakenham until the highway was changed in the 1950s to where it is now.

In 1873, Thomas Nuggent sold approximately 1 ½ acres of his land to the Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation Diocese of Ottawa for use as an RC cemetery in Pakenham. It is located on Lot 6, Conc. 9, Pakenham Township, Lanark County, atop a small hill about 2 ½ miles (4 kms) south of Village. The Indian Creek runs into the Mississippi River close to its base.

When the cemetery was begun, many skulls with long black hair were found and it was discovered that this had been the site of the old Indigenous burial grounds. An epidemic of fever/influenza brought by European settlers had wiped out many of the tribes camped along the river and the deceased had been buried high on the hill where no water could mar their graves.

They were part of the Algonquin nation whose territory includes all of Lanark County. For many years they travelled the Mississippi River. The Iroquois to the south were in conflict with other nations including the Algonquin nation, especially during the period of the colonial fur trade. In what has been called the Iroquois or Beaver wars, the tension between these First Nations grew as a result of their involvement with and growing dependency on the European fur trade. These conflicts encouraged by European settlers, the diseases that were brought from Eurasia, and the exploitation of the land not only resulted in the loss of life among many First Nations communities and peoples at the time but have continued to cause harm to Indigenous peoples and their cultures.

The cemetery that stands now is a beautifully kept scenic area in the centre of which there is a wooden cross and a large black iron cross. The cemetery was enlarged in August 1977 by a donation of land by Myrlah and Dennis Sine in order to accommodate descendants of the original families and new families in the immediate area.

For More Information About Algonquin Peoples Visit the Websites Below:

King Edward VII Among the Cedars

In 1860, King Edward VII drank here at this spring among the cedars. As Prince of Wales, he was here to lay the corner stone for the Parliament Buildings. He went on a timber raft, then on to Arnprior. A cortage of 20 carriages accompanied him to Almonte to board the train to Kingston, Almonte being the end of steel. At Bennie’s Corners he received a most royal welcome. He stopped for a drink of water and received a cold fresh drink from the spring among the cedars.

Edward was born in the morning on November 9th, 1841, in Buckingham Palace. He was the eldest son and second child of Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. He was christened Albert Edward at St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, on January 25, 1842. He was known as Bertie to the royal family throughout his life.

In 1860, Edward undertook the first tour of North America by a Prince of Wales. His genial good humour and confident bonhomie made the tour a great success. He inaugurated the Victoria Bridge in Montreal, across the St Lawrence River, and laid the cornerstone of Parliament Hill in Ottawa. The four-month tour throughout Canada and the United States considerably boosted Edward’s confidence and self-esteem, and it had many diplomatic benefits for Great Britain. At the time, his visit caused much excitement and many local activities were undertaken to commemorate his visit such as this sign which has been replaced several times. It is also recorded that a maple tree was planted to the east of Union Hall by Mr. Stevenson on honour of King Edward’s visit to Canada. Unfortunately, this massive tree was removed when the county garage was constructed by the Hall.

St. George’s Cemetery

As early as 1840, records show the Rt Rev John Strachan conducting confirmation services in the first St George’s church which was a small log church located where the present St George’s cemetery is found. The church was built on land donated by Mt Thomas James. Later on, the land was owned by Mr. Bowland and the church was often referred to as Bowland Church.

By 1869, the church was surrounded by the parish cemetery. Gradually, the parish began holding services in the village of Clayton. For many years, the log church was used in the summer and on “good” days while in the winter, services were conducted in a hall in Clayton. There is no trace left of the log church and records sadly do not tell what became of it.

The cemetery has headstones dating from 1843 and contains plots of many well-known families in the community.

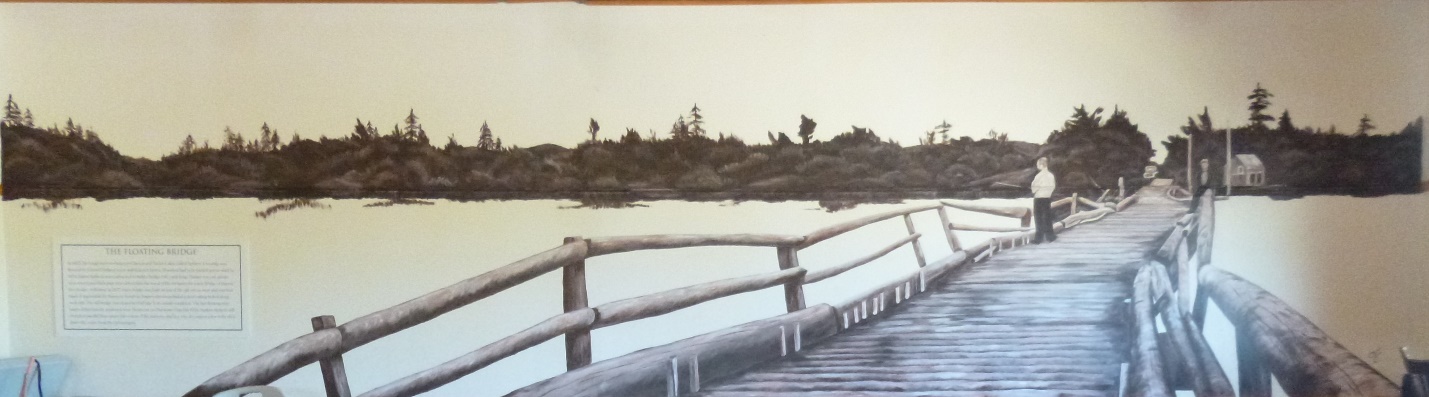

The Floating Bridge Mural

This mural across the back interior wall of Union Hall was painted and donated by Laurel Cook to commemorate this once historic landmark.

“Handy As A Pocket On Shirt”

by Claudia Smith

At the time in the history of Lanark County when travel of any sort was not easy, waterways and swamps were major obstacles to be overcome. The boggy narrows between Clayton and Taylor Lakes in Lanark Township were no exception.

Oxen splashed through the muck at a fording spot and the settlers themselves walked across on a wide plank at what was called Settlers’ Crossing. The planks were later replaced with three hewn logs chained together to make a wider bridge but it still could handle only pedestrian traffic.

In 1825, the crossing was “inundated by the backwater caused by a mill dam built by Edward Bellamy Sr.” The water level was raised by four feet and the “dry swamp” became a river.

Records show that there may once have been a ferry going across the narrows between the lakes. A Bennett family settled by the shoreline and may have operated a ferry for travelers. A local store receipt book shows that several fruit trees and garden seeds were sold to “Bennett at the ferry” in the early 1830s.

The ferry may have simply been a raft that was poled across the river carrying people and their goods. Perhaps it was a stronger, sided raft that was able to carry one horse or cow at a time. Shouts from one shore to the other may have been enough to hail the ferryman. A cord strung across the stream and attached to a bell set on a post might also have been the signal that a customer waited on the other side.

In 1858, the Lanark Township Council received a request from 69 petitioners arguing that a bridge across the river was “indispensably necessary for the convenience of the western section of the county, generally being several miles shorter by the route to the Catholic Church at Ferguson’s Falls, to Perth and to the railroad depot in Almonte.

in 1859, a contract was let to James Sullivan to build a bridge 340 yards long for 18 pounds, 10 shillings. Timber was cut, planks were sawn and thick pegs were driven into the wood of the stringers for a new bridge of an innovative design – it floated.

In August, the commissioners in charge of the project reported that “…the bridge is now finished and at present, horses and oxen with carts, wagons, buggies, carriages of all description loaded or unloaded may pass safely and securely without impediments.” On Sundays and holidays people flocked to see “…the curiosity and construction of our mammoth bridge.”

Eighteen years later in 1877, wheels wind and waves had taken their toll on the bridge. Timothy Sullivan won the contract to build a new bridge on top of the old one as it had become impossible for horses to travel on. The old arch over the waterway and the 50-foot-long passing portion on the centre of the structure were to be kept as they were in the old bridge. A stout railing was bolted along each side.

This Floating Bridge was a “handy as a pocket on a short” in summer as well as in the winter. Countless horses, wagons, farm machines, funeral processions, and people on foot, as well as sows, cows, cattle and sheep were driven over the convenient shortcut.

A woman from Galbraith area north of the lake, tapped a maple bush on the south side of the lake. She walked across the bridge carrying heavy iron pots for boiling the sap. When the sugar season was over, she carried the many pounds of sweet harvest back to her home.

There was a social life at the bridge. On evenings when parents were assured that all the chores were properly done, children ran to the river to fish.

Joe Baye, a native trapper and hunter, lived near the bridge and he always had long fishing poles to lend the youngsters.

Men fished and hunted ducks from the bridge. Families ate their packet of sandwiches on Sunday afternoon.

The bridge caught the wind like a mast in stormy weather and rocked on the waves.

In high water, the logs tended to pile up and teams of horses had to climb the logs, as did cars in later years.

When the bridge logs were bumped over in high water, children crouched on the floor in the back seat of early model cars.

Summertime brought low water and the bridge stretched down, resulting in an easier surface for travelling.

Often nerves were taut when the bridge was being navigated, especially if the horses were young and inexperienced or the load unwieldy. The men of the Miller outfit breathed a sigh of relief each time they crossed safely with their heavy threshing machine pulled by two teams of horses.

One dark and very wind night, Arthur Bar (now deceased) was heading home to the Clayton area from a festival in Rosetta. He lead his reluctant horse across the rocking bridge, nervous that the horse and buggy might go over the side or that they might fall off the end of it.

Log drives were floated from Taylor’s Lake down to the mill in Clayton and had to pass under the arch of the bridge. The Almonte Gazette reported that Mr D J Thomson took a drive of saw logs to the mill in April 1838.

“Owing to the water being so high it took three men with pike poles to put them through under the Floating Bridge. However, the trip from there to the millpond in Clayton was made in eight hours and considered a fast trip by old river men.”

The old bridge was closed by the Government of Ontario in 1943 due to its unsafe condition. People built fires on it to boil water and one group did not make sure all the coals were out.

The last floating remnants of this historic landmark were blown out on Hurricane Hazel in 1954. Sunken timbers still stretch in parallel lines under the waters of the narrows, and in a very dry season a few bolt stick above the water from the old stringers.

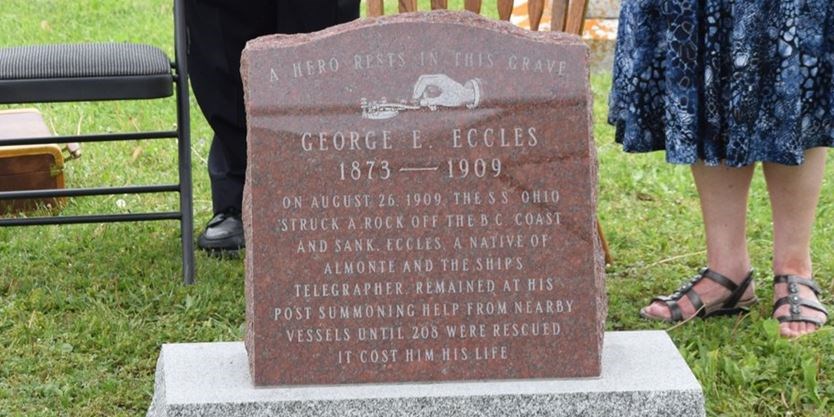

The George Eccles Commemorative Sign

The sign on Ramsay Conc 8, marks the birthplace of George Eccles, who died in 1909 while trying to save the passengers of the SS Ohio, a 340-foot steamer that struck a rock off the coast of British Columbia in the dead of an August night.

In the 30 or so minutes before the ship sank — “in the hungry maw of the sea,” wrote one excited typist — Eccles used his wireless telegraph to alert two nearby ships to the emergency and send out the vessel’s location, while frantically sticking to his duties until more than 200 passengers were safely disembarked.

In the 30 or so minutes before the ship sank — “in the hungry maw of the sea,” wrote one excited typist — Eccles used his wireless telegraph to alert two nearby ships to the emergency and send out the vessel’s location, while frantically sticking to his duties until more than 200 passengers were safely disembarked.

Even with water lapping at his feet, he is said to have gone searching for a shipmate below decks, a decision that probably cost him his life.

Heightening the drama were Eccles’ final, desperate transmissions, as reported in multiple newspapers: “Passengers all off and adrift in small boats. Captain and crew going off in the last boat, waiting for me now. Good-bye. My God, I’m …”

And there the words ended. His last breath wasn’t far behind.

Picture of George Eccles, who in 1909 sacrificed his life to save more than 200 people during a shipwreck on the S.S. Ohio off the coast of British Columbia. (Jean Levac / Postmedia News)

What is remarkable about the full Eccles tale is the way he was celebrated as a hero around the world while living his own back story of personal redemption.

In 1909, wireless transmission was a new technology, so new that Eccles is described as the first wireless operator to die in a shipping accident, just three years before the Titanic. (He is recognized in a plaque in Manhattan’s Battery Park at a monument erected to fallen “wireless boys.”)

The youngest of eight children, Eccles was born in 1873 and, as a young man, learned the new art of telegraphy from the resident CPR ticket agent in Almonte. At one point, he moved to Ottawa to be a sessional clerk at the House of Commons but wireless communication appears to have been his passion.

The skill took him to Winnipeg to work in the rail yards, then Seattle, where he hooked on with the firm that ran the SS Ohio to Alaska. While in Winnipeg, he married Nettie Barry, had two boys and was blamed, perhaps unfairly, for a workplace accident in 1905 that no doubt scarred him. One newspaper report said he had been at his telegraph station for 36 hours straight when a communication error led to a head-on train collision that resulted in at least one fatality. He was dismissed.

(Adding to the cruel timing of the sinking, too, was the fact Eccles had given notice of his resignation and the fateful trip was to be his last one.)

In Almonte, meanwhile, he was mourned like a hero for the ages. At his funeral, the town literally shut down and the mayor and councillors led hundreds in a cortege described as “the largest in the history of the town.”

The newspapers, meanwhile, tripped over themselves with portraits of glory.

“It is surely not possible that the people of Canada will let pass unheralded the steamship Ohio tragedy,” began a piece in the Montreal Star.

“Every Canadian’s breast should swell with pride at the name of Eccles. Let us know something of the man; let us help his wife and family, if he has either. Tell us of his father and mother. Don’t let him lie at the bottom of the ocean unnoticed. Eccles has shown to the world what a man’s sense of duty is.” (excerpts from Kelly Egan, Ottawa Citizen 9 Nov 2017).

GEORGE ECCLES FINALLY GETS A HEADSTONE

Although George Eccles had a large funeral ceremony, but for reasons unknown, the grave was never marked. Until 3 June 2018 (109 years later) that omission was remedied, thanks to the efforts of C.R. Gamble Funeral Home of Almonte, and Kinkaid & Loney Monuments of Smiths Falls. The headstone is located in the cemetery of St. Paul’s Anglican Church, 135 Wolfgrove Road.

The cemetery is approximately 500 metres west of the intersection of County Road 29 and Almonte Rd/Wolfgrove Road.

GEORGE C. ECCLES DAY

The community has proclaimed Aug. 26 to be George C. Eccles Day.

The Historical Settlement of Bennies Corners

In 1820, Ramsay Township was surveyed by Reuben Sherwood and associates. The survey was completed in January 1821, and almost immediately military settlers from Perth began to pour in. The first of these settlers located in Feb 1821. A large influx of settlers called the Lanark Society Settlers also arrived in late summer of 1821. These people were from Scotland and were craftsmen who had been hit hard by the depression following the Napoleonic wars.

One of the few letters which remain from those written by the Lanark Society settlers in the Ramsay township’s first year is that of Glasgow emigrant John Toshack. In a letter dated 11 Sep 1821, he said in part:

One of the few letters which remain from those written by the Lanark Society settlers in the Ramsay township’s first year is that of Glasgow emigrant John Toshack. In a letter dated 11 Sep 1821, he said in part:

“We have got land in the township of Ramsay near the Mississippi River which runs into the Ottawa about 15 miles for our land. We are only half a mile of it…….

William, John and James Bennie and I have each got one hundred acres together in a square. It is most beautiful land and resembles the Dalmarnoch haughs. According to what I have seen of other land, it will produce abundantly of all which is necessary for the support of a family….”

Bennie’s land, which later situated a crossroads point, became the village of Bennies’s Corners less than two miles from Blakeney. In the 1850s, with a population of about fifty, there was a post office and general store, a few residences, a school and tradesmen such as blacksmiths and shoemakers. William and John Baird owned a grist mill, Greville Toshack owned a carding mill and Stephen Young a barley mill, all of which were located on the Indian River.

In the 1860s Bennie’s Corners population was at its peak with about 150 people. All the original settlers were from Scotland, primarily the Glasgow and Paisley area.

From the Canadian Directory for Bennie’s Corners on in 1871, we learn that they received their mail three times a week and the following occupations were listed:

John Allan – sawmill William Anderson – farmer

John Baird – gristmill owner James Coxford –shoemaker

John Clover – cooper Robert Gomersall – tanner

Alex Leishman – post office and store Marshall – sawmill

William Phillip – blacksmith Andrew and David Snedden – grist mill

James Snedden – farmer Andrew Toshack – farmer

Toshack – shingle factory James Toshack – leather dealer

Peter McDougall – woollen factory (at Otter Glen)

Bennie’s Corners is known as the birthplace of basketball. The Schoolhouse S.S. #10 is where James Naismith and his lifelong friend, the renowned Robert Tait McKenzie, attended primary school. It is here, while playing the schoolyard game “duck on a rock”, that it is believed that James Naismith was inspired to invent the game of basketball. The famous rock is now located in the Naismith Museum housed in the Mill of Kintail (the Robert Tait McKenzie Museum) also located in the Bennie’s Corners area.

A TOUR OF BENNIE’S CORNERS (written by Jill Moxley, architectural comments by Julian Smith)

Most of the settlers in Bennie’s Corners had never farmed. They carved their living out of the bush and prospered, building the fine homes that remain today and leaving a legacy of perseverance and hard work with their descendants, many of whom are still farming in the area.

Built on the 1840s by William Moir, an early Lanark Society settler, this house is typical of the stone houses of the time, featuring an elliptical fanlight and dressed limestone quoins and door surround. There is evidence that the upper gable was added in the 1890s at the same time that the house was covered with lime stucco.

This house was originally built of logs which were later covered in wood siding and is one of the earliest homes in the area. It was the birthplace of Dr Archibald Albert Metcalfe who practiced medicine in Almonte for 65 years, served seven terms as Mayor of Almonte and pioneered the development of electrical power there.

Thus 1 ½ storey farmhouse in Vernacular Georgian style is typical of mid-nineteenth century residential design in the Valley. This house is notable for the fine cut stone used on the quoins and around the front entrance with its elliptical transom. The way the stone projects suggests that the rubble wall portion may originally have had a limestone stucco. The house was built by Walter Black and still has the original fireplace with bake oven in the cellar.

Built by William Baker in the 1850s, this house was originally of logs, later covered in wood siding. It features the typical front gable and formal entry. Note the unusual form of the transom and sidelights.

This house, which was in the Bowes family for many years, is a 1 ½ storey design, a common farmhouse style more often found in stone or brick. The symmetrical three-bay front and matching end chimneys are characteristic of mid nineteenth design.

Built by John Steele Jr in the 11890s, this house with its traditional 1 ½ story form, featuring a front gable and formal entry with sidelights and transom, is more typical of stone house of the period. The front porch was probably added early in the twentieth century. The farm is still in the Steele family.

Gatehouse of the Mill of Kintail Conservation Area. Built about 130 by John Baird as his store, it was restored and remodeled by Robert Tait McKenzie one hundred years later ad a guest lodge. Wilbert and Margaret Monette the occupied the house for approximately forty years before it was sold to the Mississippi Valley Conservation Authority. The rear addition was added in 1989.

Mill of Kintail Museum. Known originally as Woodside Mills, this imposing stone structure was built by John Baird in the 130ss as a grist mill powered by a series of dams on the Indian River. Abandoned by the Bairds in the 1860s, it was purchased by Robert Tait McKenzie in 1930 and transformed into a summer home and studio. In 1952 Major and Mrs. Leys purchased the mill and founded the museum as a memorial to Robert Tait McKenzie. In 1972 the property was purchased by the Mississippi Valley Conservation Authority.

Built in 1865 by John Snedden, son of the original settler, this house is of 3-ply brick made on the property from the local clay. It is a good example of the Neoclassical tradition with evidence of the growing interest in picturesque style evidenced by the decorative verge board and the round top sash window. Note the arched elliptical openings on the carriage house – one of the few remaining in Lanark County.

This house was built by William Toshack in about 1860 in typical Georgian Vernacular style. Note the dressed stone quoins and door and window surrounds, as well as the symmetrical end chimneys.

Home of Robert Phillip, son of the original blacksmith at Bennie’s Corners. Built in 1868, this simple frame house of three-bay design and side gable form is typical of early Ontario houses.

Schoolhouse S.S.#10 Bennie’s Corners – The first schoolhouse on this site was built of logs. The school was started in 1825 by John Bennie whose first wife and two infant children are believed to be buried here. This is the school house that Robert Tait McKenzie and James Naismith attended. It is believed that while playing the game “duck on a rock” at this school that James Naismith was inspired to invent the game of basketball. The large stone from this game has been relocated to the James Naismith Museum housed in the Mill of Kintail. The frame structure that replaced it in 1869 had a gable front design and large symmetrical windows typical of schoolhouses of the period. In 1999, a modern stone addition was added to the front of schoolhouse.

Built by William Anderson, the original settler on this farm, his house is the original log structure which has been overlaid with wood siding. The symmetry and the rectangular transom are typical of simple Classical Revival homes of log and stone. The front gable with the Gothic Revival window may have been added at a later date. The pressed metal roof probably dates to the 1930s.

This lovely stone home, now known as “Stanehive” was built in 1856 by Peter Young and his brother Robert. The quality of the stonework here is very high with cu and dressed stone laid in regular courses. A decorative effect is achieved with contrasting stone used for the quoins and the massive lintels and door surround. The large two-paneled front door is very handsome and the transom above has the uneven division typical of the area.

The Gardner farm was settled in 1821 and this house, originally of board and batten, was built in 1867 by Walter Gardner. It is a fine example of the Classical Revival style and features interesting patterning in the transom and sidelights.

Built by William Phillip, the original blacksmith at Bennie’s Corners, this L-shaped home is typical of late nineteenth century farmhouses more commonly found in central and southern Ontario. The high-pitched roof and one small gable probably originally carried fancy vergeboards of the Gothic Revival style. The round arched windows are examples of the more decorative woodwork of the late nineteenth century.

Built by Abial Marshall in the 1860s of local brick made on John Snedden’s farm, this house is an early example of the evolution from Neoclassical to Gothic Revival style. Note the Gothic window in the gable at the front and the unusual use of cut stone trim at the corners and around the window and front door.

Known as “Snedden’s Stopping Place” this substantial five-bay structure was built in 1844 to replace the original log building that burned down in 1844. The inn served the teamsters travelling up and down the Ottawa Valley and had stabling for 14 teams. It ceased operation on the late 1860s, but the farm has remained in the Snedden family and is now the home of Mississippi Holsteins.

Built in 1840 by John Toshack, one of the first settlers at Bennie’s Corners, this house is a fine example of Lanark County Vernacular. Note the elliptical fanlight and the regular courses stonework of the front façade highlighted by cut and dressed limestone quoins and door surround. The upper gable is probably a later addition.

This house was also built in the 1840s by John Toshack Jr. The unusual design features a projecting centre bay and high quality stonework. In the 1860s a very large stone addition was added to the back of the house but has since been removed.

Known as “Otter Glen” this house was built by Stephen Young in 1858. It is close to the site of his barley mill, the area’s first stone building constructed prior to 1830. The mill later became a woolen factory.

This brick house was built in 1885 and the window detail and overall style are typical of late nineteenth century design. It is the birthplace of James Naismith, the inventor of basketball. He was born in a house which formerly stood on the lot.

Built in 1855 by Robert Young, a skilled stonemason (see also #14), the house is a fine example of Vernacular Classic Revival architecture. It is known as the Naismith House since it was the home of James Naismith, the inventor of basketball. Naismith’s parents both died in 1870 and their three children were raised by their uncle and grandmother on this farm.

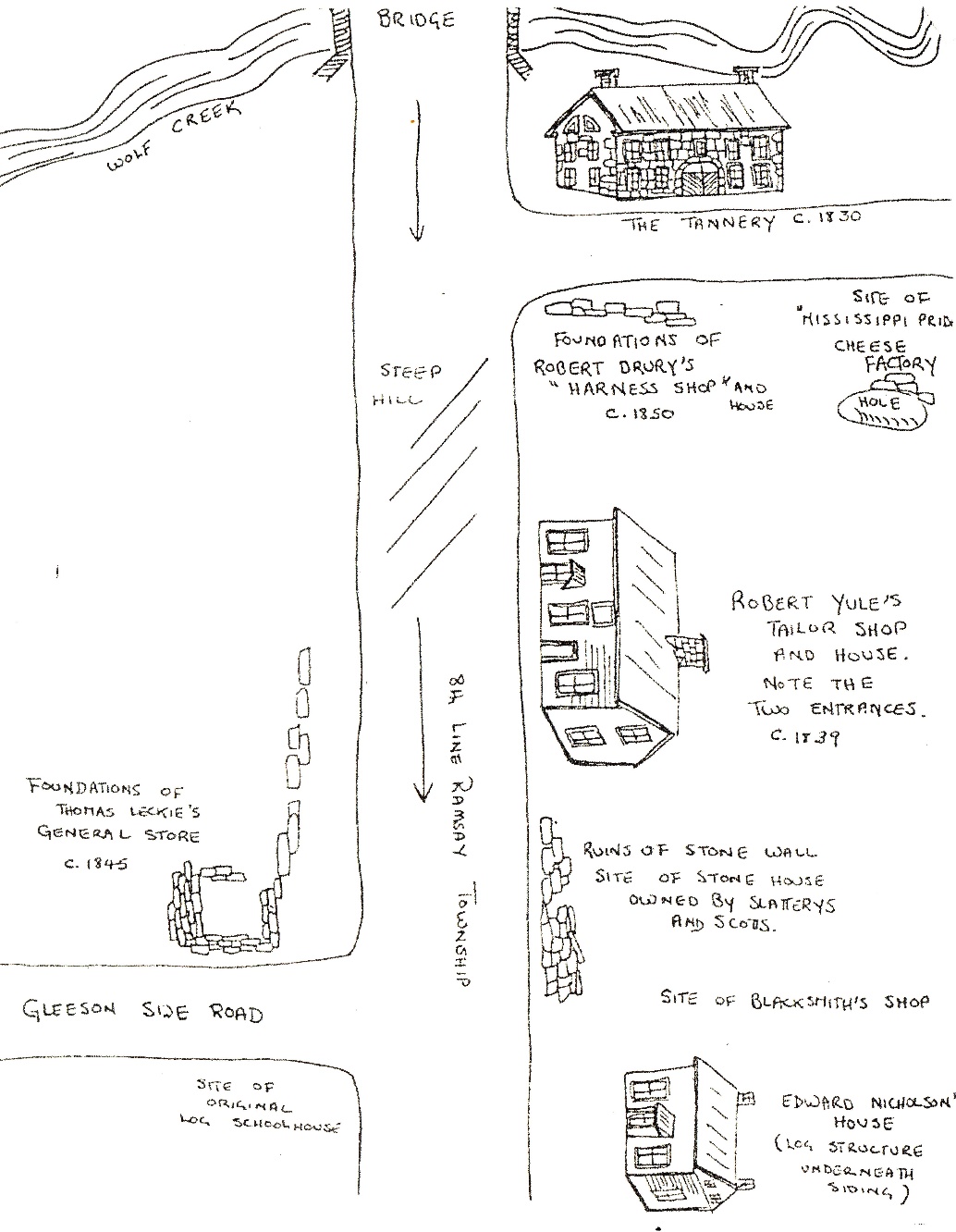

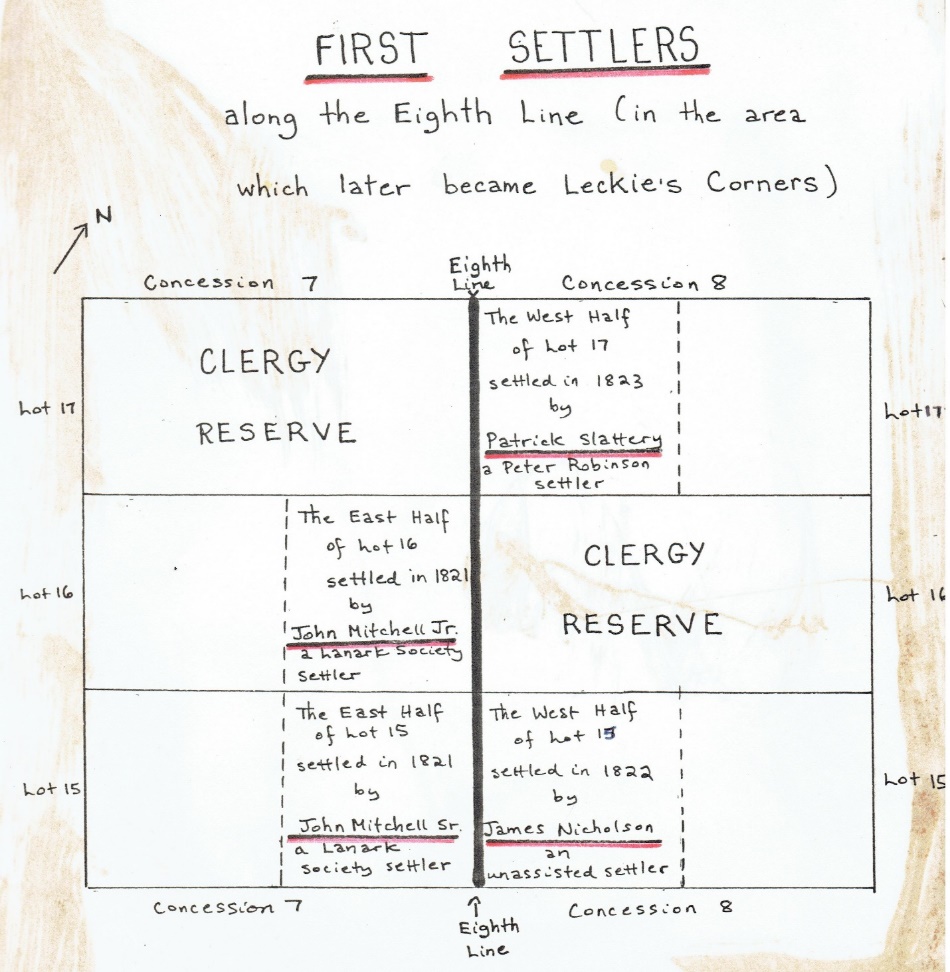

The Historical Settlement of Leckie’s Corners

In the 1840s, the area in Ramsay Township along the eight line about half a mile west of present day Almonte was a thriving community known as Leckie’s Corners. Most settlers had made their way from Perth along the Old Perth Road which was little more than a blazed footpath through dense forest. As part of all settlers’ duties, they were required to clear the road along their property which then became the 8th Line. Settlers were also to build a dwelling within the first 3 years. The first settlers were John Mitchell Jr and John Mitchell Snr who arrived in 1821. James Nicholson who arrives in 1822 and Patrick Slatery who followed in 1823.

The Importance of the Eighth Line

The Importance of the Eighth Line

In the 1820s, the Eighth Line was the main road connecting Ramsayville or Shipman’s Mills (now Almonte) with Pakenham. The Ninth Line (now Hwy 29) was only a path. The road from Morphy’s Falls (present day Carleton Place) to present day Almonte was built by statute labour in 1828. From Almonte to Pakenham, the road for many years was so bad that it could only be used for hauling supplies in winter. The road ran from Almonte to the Tannery hill on the Eighth Line and along it past the Bennie’s mill on the Indian River to Bennie’s Corners, then across to the Ninth Line at Snedden’s and on to Pakenham. With the Old Perth Road joining the Eighth Line between Lots 14 and 15, it is not difficult to imagine the Eighth Line as a most heavily travelled road. It was, therefore, only natural that schools, churches, and businesses were built along it. The present day Wolf Grove Road between Auld Kirk and Union Hall was not opened as a highway until 1967. Before that time, it was used only as a winter road.

By 1863 the community of Leckie’s Corners was well established. There was a school, a general store, a tannery, a harness shop, a blacksmith shop, a town hall and no less than three churches.

Below is a diagram (not to scale) of the significant places in Leckie’s Corners:

The Site of Old Town Hall: On this corner where this house stands, the residents of Ramsay Township, who had been holding meetings in the schoolhouse, erected a town hall in 1851 from which to conduct business. In 1916, the building was sold for lumber.

The Stepping Place: On the opposite corner where the municipal garage now stands there was a stopping house. This was a place where travelers could spend the night and stable their horses.

Site of the Old Methodist Church: The important of the church in the lives of early settlers is very apparent. Camp meetings such as the one shown below, met the social and spiritual needs of early Methodist settlers prior to the establishment of church building. Settlers were also visited by travelling ministers.

A Methodist church house, or meeting house as it was called, was a log structure built about 1835 and as one of the first churches in the area, it was open to all other denominations when not in use by the Methodists. This church no longer exists

The Free Church and Manse: Another of the community’s church built that was built in 1845/46 was known as the Free Church or Canada Presbyterian church. Land was purchased for a graveyard, church and a manse. The graveyard proved to be too stony and many bodies were moved to the Auld Kirk cemetery. The Rev William Mackenzie, father of William Tate Mackenzie was an early minister for the free church. The manse where he lived is now a private home. Twenty years later, the congregation moved to a new church in Almonte and the building was later purchased by the reformed Presbyterian church. Their minister Reverend Robert Shields, lived in the Auld Kirk manse with his wife Elizabeth, the hat maker in Leckie’s Corners. The old church was subsequently sold and became a barn. The following picture shows it in that capacity and the former manse can be seen beside. The church building was later destroyed by fire.

The Schoolhouse: ln 1856, a new stone schoolhouse was built next to the tannery. In this picture taken in 1898, the woodshed at the back of the school can be seen. It was the responsibility of the students to bring the wood in from the woodshed and keep the fire going in the school. Students also brought water to school from the nearest supply. This school served School Section Number 9 (S.S.#9). One of the early school inspectors was Rev John McMorran who became the minister at the Auld Kirk in 1846. The school was in use until 1970. The school house is now a private home.

The Tannery: The Tannery built in 1839 by Thomas Mansell who is listed as its owner in an 1851 Directory of Merchants. People from all over the area brought their Animal hides to the Tannery to be processed into leather. This involved soaking them in vats with the bark of various tress such as oak or hemlock. Tanneries were always built by a source of water that could be dammed to create a source of power to grind the bark. In this case, it was built by Woolton Creek. In 1908 it was reconfigured as the Mississippi Pride Cheese factory after fire destroyed the original cheese factory. In the 1930s it took on a new role as a dance hall for a short period of time. It had since been restored as a private residence.

Robert Drury’s Harness Shop and House: The leather produced at a tannery usually lead to the establishment nearby of enterprises that used leather. Leckie’s Corners boasted both a shoemaker and harness maker, Robert Drury, directly across the road in the 1860s. Robert Drury was born in Ireland and came to Canada with his mother and sister in 1842. It is thought that he first that he first owned a harness shop on the second floor of the Tannery. This would have been an ideal location for obtaining hides. In May 150, he purchased ½ acre of land from Thoams Mansell right across the road form the tannery and built a house and harness shop. The date that he built them is not known but an 1863 map shows the house and shop. On 28 June 1861, the following ad appeared in the Almonte Gazette.

In 1866 he moved his enterprise into Almonte.

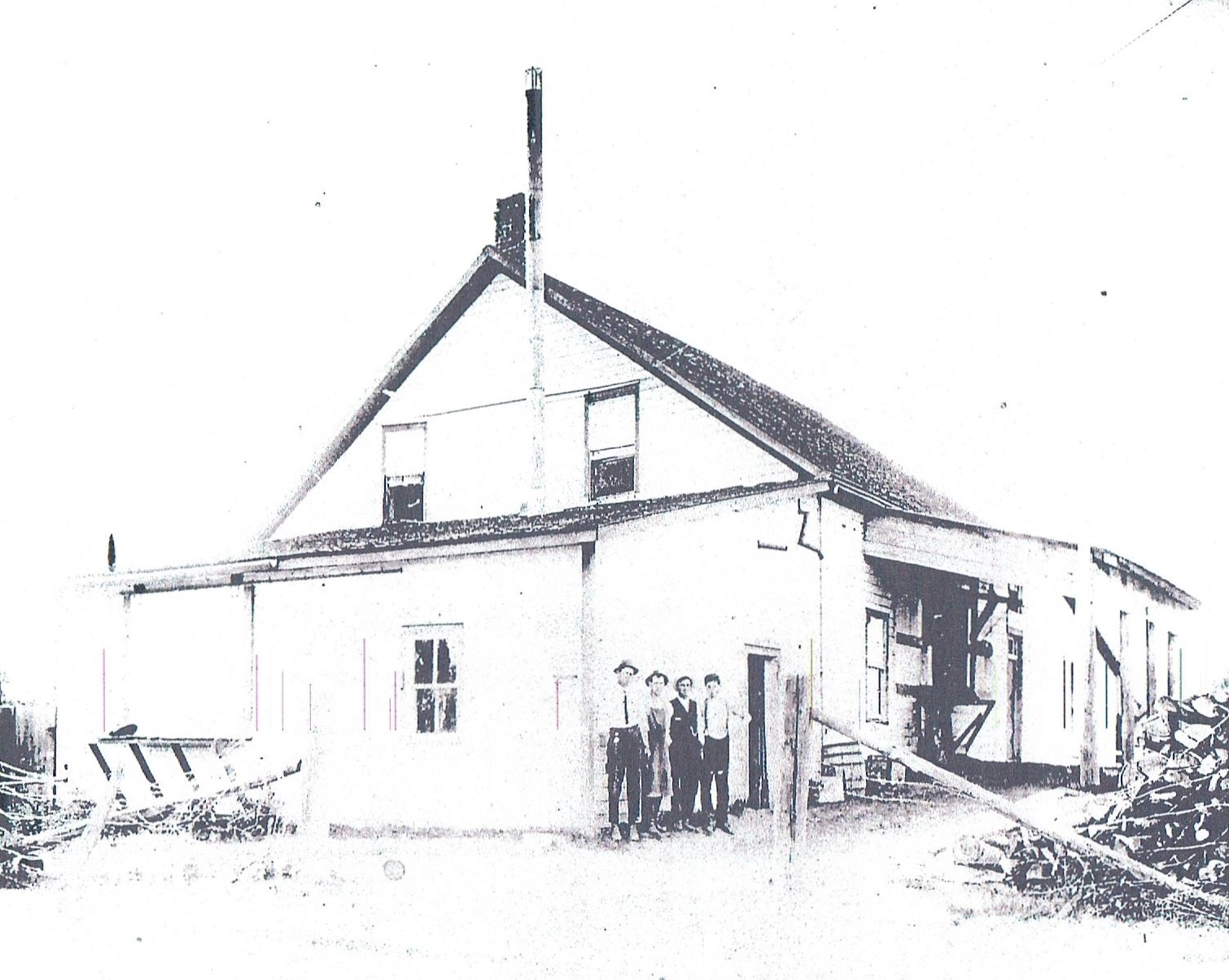

The Mississippi Pride Cheese Factory: The first cheese factory at Leckie’s Corners appears in an 1881 map. The Mississippi Pride Cheese Factory was located up the hill across the road from the tannery. Farmers brought their milk to the cheese factory daily. It was a tremendous blow to local farmers when the factory was destroyed by fire in 1908. The owners immediately made arrangements to set up business in the tannery which had been empty for some time. Within two days it was functioning as the new cheese factory. The tannery in its new capacity can be seen in the following picture. The large tub at the left side of the building is the whey vat. After dropping off their milk, the farmers would fill up their empty cans with whey to be used as feed for their livestock.

Robert Yule’s Tailor Shop: Another thriving business in Leckie’s Corners was the tailor shop. Robert Yule was the tailor at Leckie’s Corners. He was born in Glasgow, Scotland 28 May 1808. In 1821 he came to Ramsay Township with his parents James Yuill and Barbara Colton. They settled on the east half of Lot 11, Conc 6, Ramsay. He was one of 10 children.

Robert wen to the village of Lanark, where he served his tailor’s apprenticeship under Finlay McLaren. There he met McLaren’s niece, Janet, who had also come to learn the trade, and they married.

In 1839 he purchased ¾ acre in the east half of Lot 16, Conc 7 Ramsay, where he built a house with a tailor shop on one end. The two separate entrances can still be seen.

Robert was an excellent tailor which can be seen by looking at the beautifully tailored clothing in the photograph of his family.

Thomas Leckie’s General Store: The settlement was named for Thomas Leckie, a very enterprising individual. He first shows up in records in 1839 as having a license to sell liquor at his inn, the location of which is not known. In 1846, he purchased land in Leckie’s Corners and opened a general store which probably looked much like this picture. The building was eventually moved and became a machine shed. In the same building was a Milliner named Elizabeth Waddell, seen here in one of her delicate creations: (PICTURE)

Her sister Margaret operated a dressmaking business there as well. Thomas Leckie also had a cabinet making business in Almonte, sold farm equipment and operated a sawmill. Thomas Leckie also became the editor of the Almonte’s first newspaper, The Examiner. He went bankrupt during the depression of 1857 and later in 1861 he and his family emigrated to the US. This foundation is all that is left of his general store. Leckie’s General Store changed hands many times and in the late 1800s was turned into a carriage shop run by James Scott.

Ruins of Stone House Owned by Slatery and Scotts: James Scott (owner of the carriage shop located in the old Leckie’s general store) and his wife became prominent members of the Leckie’s Corners society. community. They lived in a beautiful stone house across the road. It was demolished in 1944. The stone was used in building the retaining wall for what is now known at the Heritage Mall in Almonte. All that remains today are the stones of a crumpling wall. The house had been previously occupied owned by William Slattery whose blacksmith shop was located in a building behind the house. There was room inside the blacksmith shop for a team of horses.

The Old Log Schoolhouse: Another building of importance in a community was the schoolhouse which as located within walking distance of the majority of the people. The first school in Leckie’s Corners was a log structure located at the corner of Gleeson Rd across form Leckie’s General Store.

Edward Nicholson’s House: When Ramsay was surveyed, one seventh of the land was set aside for the government and one seventh was also set aside for the Church. This was called the Clergy Reserve. And in Ramsay there were two such lots. It was hoped that as the land became more and more settled, the value of these parcels of land would increase. These clergy reserves were always a problem for early settlers since nobody lived on these parcels and therefore did not clear the road. One of these parcels was eventually purchased by Edward Nicholson who received his Crown Land Patent in 1855. His house, a log structure, still stands.

The Rosedale Union Hall Cheese Factory Mural

This mural mounted on the exterior of Union Hall was painted and donated by Laurel Cook. The Union Hall community was primarily agricultural based and so the Rosedale Cheese Factory was a very important asset to the community.

From The Record News EMC 3 Sep 1999

One of Mr. John Dunlop’s accomplishments was the building of the first cheese factory on his property in the year 1873, on the east half of the lot 16 on Concession 1 of Ramsay Township.

This replaced the old milk pan, by which cheese makers would leave milk overnight in a pan, the cream would rise to the top when cold and it would be skimmed off in a crock, when enough cream was saved to the required amount for the old dash churn.

Those old dash churns were a large crock about 10 to 12 inches in diameter and about 24 inches high. They also had a heavy crockery lid with a hole in the middle, and there was a long broom-like handle. On the bottom there was nailed a cross-piece a little smaller than the inside of the churn. This was made of a special wood; a “white bird’s eye maple”. If it wasn’t it would taint the butter.

Sometimes a worker would dash away “up and down” and keep turning the dash piece of the wood. Sometimes it would take hours before the butter would break and you would know by the sound of the dashing of the cream. Then the milk would separate from the butter and that, of course, was buttermilk, which some people really like. f the cream was sour, the butter was made faster. If the cream was sweet, it took much longer.

In 1874 on June 4 cheese was first made in the district, and twice a day the farmers drew their milk from their cows to its vats.

During 1874 and later, when the cheese was being made at the Rosedale Union Hall Cheese Factory, Andrew Stevenson would load a wagon up with 25 or 30 boxes of cheese and head for Pembroke with a team of horses. At this time the building of the railroad was in full swing and camps were set up in different places.

Cheese sold from seven cents to eight cents a pound and some of the places where he stopped they bought 10 boxes of cheese from the wagon. The best place to store it was in a trench in the ground covered over with earth; it kept quite well.

One bachelor cooked everything in the fireplace and baked beans in the sand. His name was Herb Bolton and he lived about a mile from Albert Miller’s. Oh, the smell of that fresh bread really made one hungry.

The first factory was a picturesque three-storey building with a cottage roof, and a balcony above which were four windows. (No one has pictures of this building). They were burned at the time in Wm Dunlop’s fire.

The cheese was hoisted to the third storey and kept until fall. The cheese had to be turned everyday to be kept from molding. One 75-pound cheese fell to the floor and it jut exploded when, in the fall, they were loading up to take to sell.

There was only one piece of machinery and that was the machine that chopped the curd. everything else was done by hand. Each cheese was pressed alone, and they weighed about 75 pounds each.

The water supply came from a spring on the Dunlop property, and was piped down to the cheese factory by the use of tamarack poles five to six inches in diameter and about 20 feet long. They were bored by a steel auger and were driven by horse power, from one end to the other of these tamarack poles. They were put together with space piping. A blacksmith made the ring to seal each joint, and it was about 200 yards north.

In the autumn the cheese was shipped to market. Now the cheese is turned everyday and shipped every week when they are eight days old.

Later, Mr. Everett went into partnership with Mr. Dunlop and together they made repairs. They removed the top storey, which was then Mr. Wm. Dunlop’s garage (his son’s).

They installed steam pipes and put in a new plank floor. They had a steam pump to pump the whey into a tank outside. A new vat and boiler were installed in 1888. A few years later the cement floor and steel roof were added. The steel roof still remains on the building but has now been painted.

The first cheese was very soft as it was heat-cured. However, there have been great improvements made since those days.

Mr. Albert Graham Miller was interested in learning how to make cheese, and he went to work at the cheese factory in 1901. He was 15 or 16 years old, but it was John B. Wylie who owned the factory then, with Jack Hitchcock being the cheese maker and Miller worked under his supervision.

Mr. Albert Graham Miller has since been deceased but was a patient in the Almonte Hospital for many years. He was blind, but what a fantastic memory. He was in his late 90s and was married to the late May Anderson from Middleville. They had three sons and he made cheese for 44 years in various cheese factories.

In 1927 John B. Wylie sold the Union Hall or Rosedale Cheese factory to Producers Dairy, In 1936, Alec Moses, cheese maker, then won the John Echlin Cup for the most amount of cheese ever sold on the Perth Board in Lanark County. The “Echlin Cup” was donated by Mr. Echlin, the cheese inspector.

In 1949 George Affleck, who lived in Clayton, came very close to winning the Echlin Cup for the highest average score in Lanark County.

In later years the tamarack poles were replaced with galvanized piping, but the spring water still ran into a tank in front of the cheese factory for many years. Winter and summer the farmers watered their horses there.

Mr. Archie Robertson, who lived across the road, got his drinking water there, and also Mr. Roy Robertson’s family. They never had a well, just a cistern and a pump in the house for the needs of water other than drinking.

In 1933, a well was drilled at the factory. There was also a lean-to at the north end of the factory where they put ice.

The weigh tank was on the south side of a corner of the factory and was sunk into the ground three to four feet deep.

The cheese boxes were made by Bill Nichols in Carleton Place and cost ten cents each in 1910 – 1913. They had a huge basket rack and a team of horses that would bring a load of 400 cheese boxes at once to Rosedale Union Hall Cheese factory.

In 1928 there were 41 patrons at Rosedale Union Hall Cheese Factory. The number of cows totaled 410. The average selling price for cheese was 21.2 cents per pound and the average price for whey butter was 36 cents a pound.

The depression years brought hard times and in 1932 cheese sold for 9.49 cents a pound and whey butter for 10.22 cents a pound. Gradually during the thirties, production and prices increased. In 1943 there were 55 patrons sending their milk to the factory.

In 1946 the patrons of Rosedale bought the factory from the Producers Dairy at a cost of $2350 and a new cheese factory was built across the road in 1947 by the farmers of Union Hall district.

The Historical Settlement of Union Hall

Unlike most of the other settlements in the area that were founded around mills, Union Hall settlement was a farming community. The history of this settlement is told through the various properties in the area.

#1792 Wolf Grove Rd – The Union Hall School was located on this site from 1847 until its closure in 1964 after which the building was moved to the Ramsay Township municipal offices where it was used as a maintenance garage. It was demolished in 2017. Education was a priority for early settlers and not surprisingly, the Union Hall School has an early, varied, interesting and sometimes controversial history.

#1792 Wolf Grove Rd – The Union Hall School was located on this site from 1847 until its closure in 1964 after which the building was moved to the Ramsay Township municipal offices where it was used as a maintenance garage. It was demolished in 2017. Education was a priority for early settlers and not surprisingly, the Union Hall School has an early, varied, interesting and sometimes controversial history.

More on the story of Union Hall School

# 1905 Wolf Grove Rd – Sutherland’s farm (now called Hobby Horse Farm). The first owner who received the original crown grant was Jock Sutherland, a Highlander with Jacobite ancestors who came with his wife from Glasgow. They could speak both Gaelic and English. His son, William, married Margaret Campbell, who was the daughter of a veteran of the Crimean War who was the first president of the Almonte Fair and was also a magistrate. The first post office for Union Hall was kept in the Sutherland home. The window frame had a slot cut into it through which letters were dropped. The mail came from Clayton. Later the post office was moved to the Penman home. The telephone came in 1908. Rural mail delivery started in 1911. The farm passed out of the Sutherland family ownership with its sale in 1980.

Union Hall was at the center of a community known as Union Hall Settlement. Union Hall has always been more than a mere building; it has been a symbol of rural community spirit for over 150 years.

In 1835, Lot 16, Concession 2 of Ramsay Township was deeded to Sophia Thom. Some of this land was acquired by the directors of the Ramsay & Lanark Library in November 1856, and in the spring of 1857, a frame building was erected as a library and a church – “a hall for all denominations."

Education was a priority for the early settlers. Although a log school had been built on 1847, the community welcomed this new building and the newly-formed “Library and Literary Association” because in 1857, many children in the School Section # 3 Ramsay were unable to read or write. Acquiring books was important and by 1869, the number of books in the libraries of Union Hall, the School and the Sunday School totaled 815 volumes.

The hall quickly became a focal point in the Community. The Sons of Temperance Society met there from the mid-1800s into the early 1900s and according to the convention, the ladies always sat on the right side of the room and the gentlemen on the left. The society displayed a large membership chart and had temperance mottos printed in big black letters on the walls. A sample of these might have been ” Hell is populated with the victims of ‘harmless’ amusements – the bottle, the weed, and the cards.”

Mr Joe Dougherty held a singing school in the hall and children learned to read music and sing four-part harmony. In the late 1800s there was a Union Hall String Band and music became an integral part of all social events.

In the 1880s teacher John Clelland operated a grange (or co-op) at Union Hall. Farming families who belonged to the grange purchased groceries in bulk and picked them up on Saturdays.

In 1919, under the guidance of teacher Howard Allison, the Union Literary Society was formed. It met in the hall every second Saturday night to read plays, debate and present papers on interesting subjects. The members put together a jocular and gossipy newspaper called The Literary Review. A motion was passed that members “not get sore over remarks in the paper."

The hall was the home of the Union Hall Tiger Baseball Club from around 1915 to the 1940s. Baseball was popular at community picnics and festivals and many the cow was milked in a hurry so that young ball players could get to the games. With no field lights, starting times were early to get the games in before dark. There was also a Junior Women’s Institute girls’ ball team called the Janey Canucks.

The Union Hall Women’s Institute was formed in 1932. With humour and music, its members helped each other through the hard time of the Depression and the grim years of World War II. They improved the hall by extending the stage and building an anteroom in which to perform plays. Historically, there had been no dancing in the hall; however; the Institute’s members wanted to hold dances, and having saved the place from falling down, asserted that it was their right to do so.

In the 1940s variety concerts “packed the hall to the doors” under the guidance of Made Robertson who was “so good at getting them up”. Horses were tied along the fences in warm weather and stabled in nearby barns in the winter. There were no babysitters so children were taken along. Babies were bundled into the corner of the hall to sleep away the evening as square dances were called, plays or concerts were performed or box socials were enjoyed.

A new floor was laid in the 1950s to improve the dancing surface. It may have been around this time that a square grand piano was acquired. The hall’s unheated environment was not suitable to a piano over the years and in 1991, a motion was passed “to compassionately dispose” of it and it was sold.

As the years went by, the Union Hall Community did not let the hall wain. In 1988 a new roof was put on and a septic system was laid out. An addition with a kitchen, toilets and a handicapped access was built by volunteers in 1989 and the Union Hall Community Centre was incorporated.

Dances, Halloween parties, music and talent nights as well as banquets, corn roasts, pancake breakfasts and strawberry socials have kept the hall vital. When Ontario Hydro proposed a transmission line through the community, the voices of the Union Hall Action Committee was successfully raised in opposition.

The Rosedale Union Hall Cheese Factory

From The Record News EMC 3 Sep 1999

One of Mr. John Dunlop’s accomplishments was the building of the first cheese factory on his property in the year 1873, on the east half of the lot 16 on Concession 1 of Ramsay Township.

This replaced the old milk pan, by which cheese makers would leave milk overnight in a pan, the cream would rise to the top when cold and it would be skimmed off in a crock, when enough cream was saved to the required amount for the old dash churn.

Those old dash churns were a large crock about 10 to 12 inches in diameter and about 24 inches high, They also had a heavy crockery lid with a hole in the middle, and there was a long broom-like handle. On the bottom there was nailed a cross-piece a little smaller than the inside of the churn. This was made of a special wood; a “white bird’s eye maple”. If it wasn’t it would taint the butter.

Sometimes a worker would dash away “up and down” and keep turning the dash piece of the wood. Sometimes it would take hours before the butter would break and you would know by the sound of the dashing of the cream. Then the milk would separate from the butter and that, of course, was buttermilk, which some people really like. If the cream was sour, the butter was made faster. If the cream was sweet, it took much longer.

In 1874 on June 4 cheese was first made in the district, and twice a day the farmers drew their milk from their cows to its vats.

During 1874 and later, when the cheese was being made at the Rosedale Union Hall Cheese Factory, Andrew Stevenson would load a wagon up with 25 or 30 boxes of cheese and head for Pembroke with a team of horses. At this time the building of the railroad was in full swing and camps were set up in different places.

Cheese sold from seven cents to eight cents a pound and some of the places where he stopped they bought 10 boxes of cheese from the wagon. The best place to store it was in a trench in the ground covered over with earth; it kept quite well.

One bachelor cooked everything in the fireplace and baked beans in the sand. His name was Herb Bolton and he lived about a mile from Albert Miller’s. Oh, the smell of that fresh bread really made one hungry.

The first factory was a picturesque three-storey building with a cottage roof, and a balcony above which were four windows. (No one has pictures of this building). They were burned at the time in Wm Dunlop’s fire.

The cheese was hoisted to the third storey and kept until fall. The cheese had to be turned everyday to be kept from molding. One 75-pound cheese fell to the floor and it just exploded when, in the fall, they were loading up to take to sell.

There was only one piece of machinery and that was the machine that chopped the curd. Everything else was done by hand. Each cheese was pressed alone, and they weighed about 75 pounds each.

The water supply came from a spring on the Dunlop property, and was piped down to the cheese factory by the use of tamarack poles five to six inches in diameter and about 20 feet long. They were bored by a steel auger and were driven by horse power, from one end to the other of these tamarack poles. They were put together with space piping. A blacksmith made the ring to seal each joint, and it was about 200 yards north.

In the autumn the cheese was shipped to market. Now the cheese is turned everyday and shipped every week when they are eight days old.

Later, Mr. Everett went into partnership with Mr. Dunlop and together they made repairs. They removed the top storey which was then Mr. Wm Dunlop’s garage (his son’s).

They installed steam pipes and put in a new plank floor. They had a steam pump to pump the whey into a tank outside. A new vat and boiler were installed in 1888. A few years later the cement floor and steel roof were added. The steel roof still remains on the building but has now been painted.

The first cheese was very soft as it was heat-cured. However, there have been great improvements made since those days.

Mr. Albert Graham Miller was interested in learning how to make cheese, and he went to work at the cheese factory in 1901. He was 15 or 16 years old, but it was John B Wylie who owned the factory then, with Jack Hitchcock being the cheese maker and Miller worked under his supervision.

Mr. Albert Graham Miller has since been deceased but was a patient in the Almonte Hospital for many years. He was blind, but what a fantastic memory. He was in his late 90s and was married to the late May Anderson from Middleville. They had three sons and he made cheese for 44 years in various cheese factories.

In 1927 John B Wylie sold the Union Hall or Rosedale Cheese factory to Producers Dairy. In 1936, Alec Moses, cheese maker, then won the John Echlin Cup for the most amount of cheese ever sold on the Perth Board in Lanark County. The “Echlin Cup” was donated by Mr. Echlin, the cheese inspector.

In 1949 George Affleck, who lived in Clayton, came very close to winning the Echlin Cup for the highest average score in Lanark County.

In later years the tamarack poles were replaced with galvanized piping, but the spring water still ran into a tank in front of the cheese factory for many years. Winter and summer the farmers watered their horses there.

Mr. Archie Robertson, who lived across the road, got their drinking water there, and also Mr. Roy Robertson’s family. They never had a well, just a cistern and a pump in the house for the needs of water other than drinking.

In 1933, a well was drilled at the factory. There was also a lean-to at the north end of the factory where they put ice.

The weigh tank was on the south side of a corner of the factory and was sunk into the ground three to four feet deep.

The cheese boxes were made a Bill Nichols in Carleton Place and cost ten cents each in 1910 – 1913. They had a huge basket rack and a team of horses would bring a load of 400 cheese boxes at once to Rosedale Union Hall Cheese factory.

In 1928 there were 41 patrons at Rosedale Union Hall Cheese Factory. The number of cows totaled 410. The average selling price for cheese was 21.2 cents per pound and the average price for whey butter was 36 cents a pound.

The depression years brought hard times and in 1932 cheese sold for 9.49 cents a pound and whey butter for 10.22 cents a pound. Gradually during the thirties, production and prices increased. In 1943 there were 55 patrons sending their milk to the factory.

In 1946 the patrons of Rosedale bought the factory from the Producers Dairy at a cost of $2350 and a new cheese factory was built across the road in 1947 by the farmers of Union Hall district.

Union Hall School

(From Log Book of Union Hall by M. Jean Stewart and A Story of Union Hall Public School by Lloyd Sutherland)

Another Union Hall institution with an early and varied history is it school. The School Act of 1841 established Union Hall settlement area as School District #7 (re-organised in 1855 as School Section #3). A ratepayers meeting was held in 1843 to determine the location of the school. Some ratepayers (from what later became S.S. #6&7) wanted the school to be built on a site at the corner of the road to Ramsayville (later named Almonte) and Conc. 4. To counteract this suggested site, the ratepayers from Conc. 1 and 2 commenced building a school by laying a foundation for the school directly across the road south of the present day Union Hall. This site was rejected in a tie vote at a ratepayers meeting in 1843. A compromise was worked out and a schoolhouse was built at the property now identified as 1792 Wolf Grove Rd. on ¼ acre property purchased from Mr. William Sutherland. In 1847, a log schoolhouse was constructed measuring about twenty square feet (about half the size of the replacement schoolhouse that was in use from 1868 until 1964). In spite of that fact, the attendance then is said to have varied from 60 to 100.

Picture a rough log building with a cottage roof, tall chimney, pine plank floors and no sheltering porch or woodshed. Equipment, too, was poor. The scholars sat in two rows of benches, half the width of the room in length. With one narrow aisle down the centre. Eight or ten students sat in each row and wrote with slates and slate pencils on desks as long as the benches nailed to the wall at one end, The teacher sat on a high four-legged stool and used a blackboard which stood on 2 legs and leaned against the wall. On winter days each pupil brought a quantity of wood to burn in the box stove. Miss Jessie Paul, the last teacher n the old school, must have been glad when it became outdated and plans for the building of a new school were made.

But the building of the new school was not without some controversy. At the time, Huntersville was a busy little settlement with a woolen factory. In 1868 some of the ratepayers in parts of SS#3 and SS #6&7 petitioned to create a new school district centered around Huntersville. There was at the time, a cement school that had been built on the road from Clayton to Almonte that served SS #6&7. Those petitioning for a new school section started a foundation at the corner of the Clayton Rd and Conc. 4. It was later decided not to create this new school section so SS#3 was clear to start plans to build a new school. At one point it was thought to build the new school across the road south of Union Hall but if the new school were built there, the children on and past Conc. 3 could attend school SS #6&7 in the summer but would have to go to SS#3 in the winter. So it was decided to build the school on the old site. The new school was built in 1870 at an expense of 4627. The schoolhouse was erected on the SE corner of the school site. It measures 40 ft long, 27 ft wide and the ceiling was 12 ft high. The old log schoolhouse was bought by Mr. Robert Giles and moved to his farm. Additional property was also bought from Mr. Sutherland.

When the school was closed in 1964, it was purchased in 1965 by the Ramsay Township and moved to the Township lot on Conc. 8 where it became a garage and storage facility for the Township equipment. Unfortunately, just before the contractor commenced the move, it was discovered that the building would interfere with the Hydro lines during the move and the roof had to be lowered down on it plates at considerable additional expense to the township.

The schoolhouse was eventually demolished in 2017.

The Union Hall Women’s Institute Historical Mural

This mural mounted on the exterior of Union Hall was painted and donated by Laurel Cook to commemorate the Union Hall Women's Institute.

The Union Hall Women’s Institute was formed in 1932. With humour and music, its members helped each other through the hard time of the Depression and the grim years of World War II. They improved the hall by extending the stage and building an anteroom in which to perform plays. Historically, there had been no dancing in the hall; however; the Institute’s members wanted to hold dances, and having saved the place from falling down, asserted that it was their right to do so.

The Union Hall Women’s Institute was formed in 1932. With humour and music, its members helped each other through the hard time of the Depression and the grim years of World War II. They improved the hall by extending the stage and building an anteroom in which to perform plays. Historically, there had been no dancing in the hall; however; the Institute’s members wanted to hold dances, and having saved the place from falling down, asserted that it was their right to do so.

Monthly Institute meetings kept to a strict agenda. Roll calls and mottos were regular features. Inspirational ideas were presented. Individual members would present a motto such as “Worry is like a rocking chair, it doesn’t get you anywhere.” During the “dirty thirties”, there was much worry in the community, but the WI’s minutes during that time speak of basket picnics to the lake, afternoons of races, contests and ball games and quilting after meetings amid much laughter and cheer.

A travelling library was set up in 1934 and quite an exchange of books was recorded. Fundraising parties were also held.

Young children were brought to the meetings in the early days and there was “no thought of a thing called a babysitter“ then. The men came to meetings held in the evening, playing cards in another room while the women conducted their business. In October 1946, they were rewarded at the end of the meeting, the motto presented at that meeting was “Bring a pumpkin pie, the recipe and a husband to help eat it.”

The years of WWII were stressful on the community. Some families had 2 or 3 of their offspring off at war. The war-work committee raised money for the Red Cross with dances, progressive euchre parties and checkers. Patriotic songs were sung and quilts quilted for the war fund. Christmas boxes were sent overseas to service personnel.

Cooking fat was one of the things that was salvaged. Oils for making explosives were no longer available from the Far East. Homemakers were urges to save fata a 40 million pounds were needed each year. It took 350 pounds to produce enough glycerin to fire a shell from a big Naval gun. “The hand that holds the frying pan will win the war”, Women’s Institute members were told.

Following the war, came the request for food parcels and clothing for European people suffering the devastation of war. Through the years, continued with friendship and fun, cooperation, worthy causes and stimulating projects. The Union Hall WI finally closed in the 1990s.

The Historical Settlement of Huntersville

Huntersville was a small hamlet down the Indian River from Clayton on Lot 21 Conc. 4 Ramsay. In the early years before 1872 it was referred to as Hunter’s Mills. The Almonte Gazette consistently refers to it as Huntersville. However, the Canada Post records and the 1881 Belden Atlas call it Huntersville. Land records for this piece of land are confusing at best, as both the East and West halves are noted in the same document. The bulk of the ruins lie in the East half, but the records show that the Hunter family also owned part of the West half as well. The ruins include remnants of an old mill, the foundation of the post office and two houses. As well there is still standing next to Clayton Rd, just west of the Chute Bridge, an old log house that is still occupied. This property in the land records is referred to as being 6336 square feet. It was sold by John Bowland in 1875 to Alexander Hunter. It is said that there was also another house beside this house.

As well, there was a school, S.S. # 16 Ramsay. It was on the fourth line, but the exact location of this school is not. It was noted in the Minutes of Ramsay Freeholders and Householders on May 30, 1868 that a petition by Robert McClennan and others praying for the formation of a new school section near Hunter’s Woollen Factory. The section formed was from parts f No. 3 and No 6&7. A Clayton carpenter, Daniel Watt told in his diary of building the School there on 1870 for $100. The following year he built a house for the Hunters for $800 but $100 of it was never paid.

As well, there was a school, S.S. # 16 Ramsay. It was on the fourth line, but the exact location of this school is not. It was noted in the Minutes of Ramsay Freeholders and Householders on May 30, 1868 that a petition by Robert McClennan and others praying for the formation of a new school section near Hunter’s Woollen Factory. The section formed was from parts f No. 3 and No 6&7. A Clayton carpenter, Daniel Watt told in his diary of building the School there on 1870 for $100. The following year he built a house for the Hunters for $800 but $100 of it was never paid.

In 1861, the census of Ramsay listed John Hunter, a 30 year old spinner and his wife Margaret also aged 30, their one year old son, James, along with James Hunter aged 54, a wool sorter and his wife Janet, as well as Alexander aged 24. They all lived together in a frame house. By 1871, Alexander has a wife, Isabella and is listed as a manufacturer. Unfortunately, the 1861 census does not tell us exactly where they were living but in 1871, they were definitely in the property.

The first land transaction that we see for this property involving the Hunter name took place on 27 February, 1865 when John Hunter bought 33 ½ acres from George Manson. Although the records say this was part of the West Half of Lot 21, the ruins are clearly on the East half of the lot.

The Hunters built a woollen mill on the edge of the river. Their first advertisement appeared in the Almonte Gazette in October 1867 when they announced the opening of their Woollen Factory where they would do all kinds of custom work: Carding, spinning, weaving, fulling and finishing. They also stated that they have long experience in the business, and have the very best machinery, and a good assortment of Country Cloths. From 1867-1881, John Shaunessy was superintendent of the mill.

Huntersville Post Office opened December 1, 1871 with John Hunter as postmaster. He served until October 16, 1874. His brother Alexander took over on January 1, 1875 and served until March 1, 1880 when the post office closed because no one could be found to serve as postmaster. It was reopened on January 1, 1885 when John Spiers oved to the settlement and tool on the job. He lasted until January 5, 1892 when he resigned. Robert McLellan served from July 5, 1892 until his death in May of 1913. Subsequently, Edward McLellan served from June 26 1913 until Rural Mail delivery was instituted on September 17, 1913.

Huntersville became known as Jamieson in 1885 because the mail for Huntsville became confused with that of Huntersville. Even though the change of the name to Jamieson was made in 1885, the area continued to be referred to as Huntersville for many years afterwards.

By 1872 the brothers, John and Alexander Hunter were feeling confident enough in their business to expand and purchased the woollen mill in Almonte known as No. 3 Mill, which had been previously leased by Mr. L.C. Northrup who had retired. It was noted in the Gazette that the mill at Huntersville was for sale.

The business in Almonte did not go well and by January of 1873 was in the hands of an assignee. Then the real disaster struck. The mill in Huntersville was totally destroyed by fire on the evening of January 27, 1873. All the workers had left the factory except for the superintendent who noticed the flames bursting through the belt holes from the lower floor, and so rapid was the progress of the flames that it was with difficulty that he escaped from the building and before any assistance arrived, the whole factory was enveloped in roaring flames. There was a small machine shop on the opposite side of the creek, owned by Mr. Manson. It became evident that the fire would soon consume it also. The neighbours and factory hands speedily removed the contents of the shop, but the building caught fire and was entirely consumed. The loss on the building and machinery was about $8000 while the cloth and raw material was bout $2500. Insured only $3500 in the Western.

In the spring and summer of 1873, the brothers were rebuilding the mill.

The property in Almonte was sold as a Mortgage sale. As well, as part of their insolvency proceedings, the part of the West half of Lot 21 in the Fourth Concession containing the one half acre with a good dwelling house, was advertised in the Gazette for sale.

Life in Huntersville went on. In 1874, Robert Allan advertised tat he was running a Shingle and Carding mill at Huntersville. The Hunter brothers dissolved their partnership. Although nothing is shown in the land records, a company called Simpson & Co advertised that they had purchased the Woollen Mill at Huntersville in May of 1879. The mill was to be under the management of E. Charbonneau. However, this did not last long because by January of the following year, the factory was advertised by W.J. Bowland of Clayton “for sale or rent", the Woollen Factory at Huntersville, also 33 acres of land and a dwelling hose.

IN 1892, the mill was run by Wm. Croft and Son of Middleville. During this time, Mr. John Reid was in charge. At the end of 1902 the mill closed.

The final mention of the School appears in the Gazette in 1909 : SCHOOL HOUSE FOR SALE.

The final chapter to the mill appears in the Gazette in 1919: Tenders will be received by the undersigned up to the 10th of February for the mill building at Jamieson which contains a large quantity of good lumber and frames suitable for a barn, etc.

Today there is only the one log house left, as well as ruins of foundations of the mill, homes and post office.

Contact Us

MUNICIPAL OFFICE

3131 Old Perth Rd

Box 400

Almonte ON, K0A 1A0

Email: Town@mississippimills.ca

Phone: 613-256-2064

HOURS OF OPERATION

Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. except on Statutory Holidays

Sign up to our newsfeed